No, Ethereum Name Service is still a clown show

Note: This post is about the technical design of ENS, i.e. how it’s supposed to work in theory. I do not cover the numerous implementation issues, i.e. how it actually works in practice. That would be an entire other post, but those issues are (at least theoretically) fixable.

Disclaimer: I am involved with a competing project. Since I am not in the business of shilling cryptocurrencies, I am not going to name it, though it’s not exactly a secret. I was not paid anything to write this article, I just like laughing at clowns on the Internet.

What is ENS?

ENS (the “Ethereum Name Service”) is a blockchain-based naming service. It markets itself1 as a censorship-resistant and decentralized naming system.

Prior to November 10, 2021, this was a direct lie. While promoters continually represented it as being such, in actuality, the entire contract was controlled by a 4-of-7 multisig, who had total power2 to seize any domain (including for trademark reasons, or because they received a forged court order), and which publically announced3 their intention to do so if it came to it.

Quote:

PAUL WOUTERS [IETF]: Sure. Paul Wouters, IETF. So I have a question. Let’s say IETF gets the domain IETF in this naming system and we pay our fees for a couple of years. Everybody uses the site. And then at some point, we forget to pay and the domain falls back into the pool and then somebody else registers it and we don’t know where they are or who they are. Now I go to a court system. I get some legal opinion saying I own this trademark and now I want to get this domain back. Is there any way for me to get this domain back?

LEONARD TAN [ENS developer]: So right now, the ENS industry, you can change it because it requires four out of seven people. Most of them are Ethereum developers. And it is a consensus for several of them to make any changes. So it is possible, but it is going to be a very difficult thing to do but it is possible.

On November 10, ENS changed its “governance structure” to a DAO (“Decentralized Autonomous Organization”). The underlying intent was presumably to solve these problems.

This naturally raises the question: are the problems solved? Is ENS now (1) decentralized and (2) censorship-resistant?

TL;DR: (1) depends on your definition, and (2) not by any stretch of the word.

Two ways to skin a cat

The Bitcoin whitepaper never directly mentions (de)centralization. It does, however, mention “trusted third parties” a great deal. The closest we come to a definition is this: (emphasis added)

I’ve developed a new open source P2P e-cash system called Bitcoin. It’s completely decentralized, with no central server or trusted parties, because everything is based on crypto proof instead of trust. Give it a try, or take a look at the screenshots and design paper: Download Bitcoin v0.1 at http://www.bitcoin.org

…

Privacy could always be overridden by the admin based on his judgment call weighing the principle of privacy against other concerns, or at the behest of his superiors. Then strong encryption became available to the masses, and trust was no longer required. Data could be secured in a way that was physically impossible for others to access, no matter for what reason, no matter how good the excuse, no matter what.

— Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin open source implementation of P2P currency

We’ll call this, in want of a better term, “anarchic decentralization”. The power is moved from a monarch, a single point of failure, but it’s moved to nowhere. For example, who owns Bitcoin? Nobody! People may own bitcoins, but even if you had all 21 million of them, it’s not like you could show up at the annual general meeting and demand changes.

Bitcoin is not really a currency with certain rules, but rather a set of rules with a currency attached to it.

In the words of Carl Schmitt, sovereign is he who decides on the exception. But in Bitcoin, there is no trusted third party. There is no decision to be made, and there is never any exception to or reprieve from the rules.

The reason that this is possible is that the rules can be enforced 100% mechanistically. Because a computer can enforce them, no human is needed to. Because no human is needed in the loop, there is no need for a governance procedure, or any of these other squishy institutions - only cold, hard code. Bitcoin is not decentral as much as it is acentral.

The other type is, shall we call it, oligarchic decentralization. Here, decentralization simply means that there is no single point of failure. This is a much weaker property. Here, we are not concerned with eliminating trusted third parties, but rather in ensuring there’s many of them across which to spread out the trust. A lot of things are “decentralized” in this weaker sense:

- The SWIFT system - made up by more than 11,000 financial institutions

- The European Union - made up of 27 countries

- JPMorgan Chase - owned by what is surely millions of shareholders

Which one is ENS?

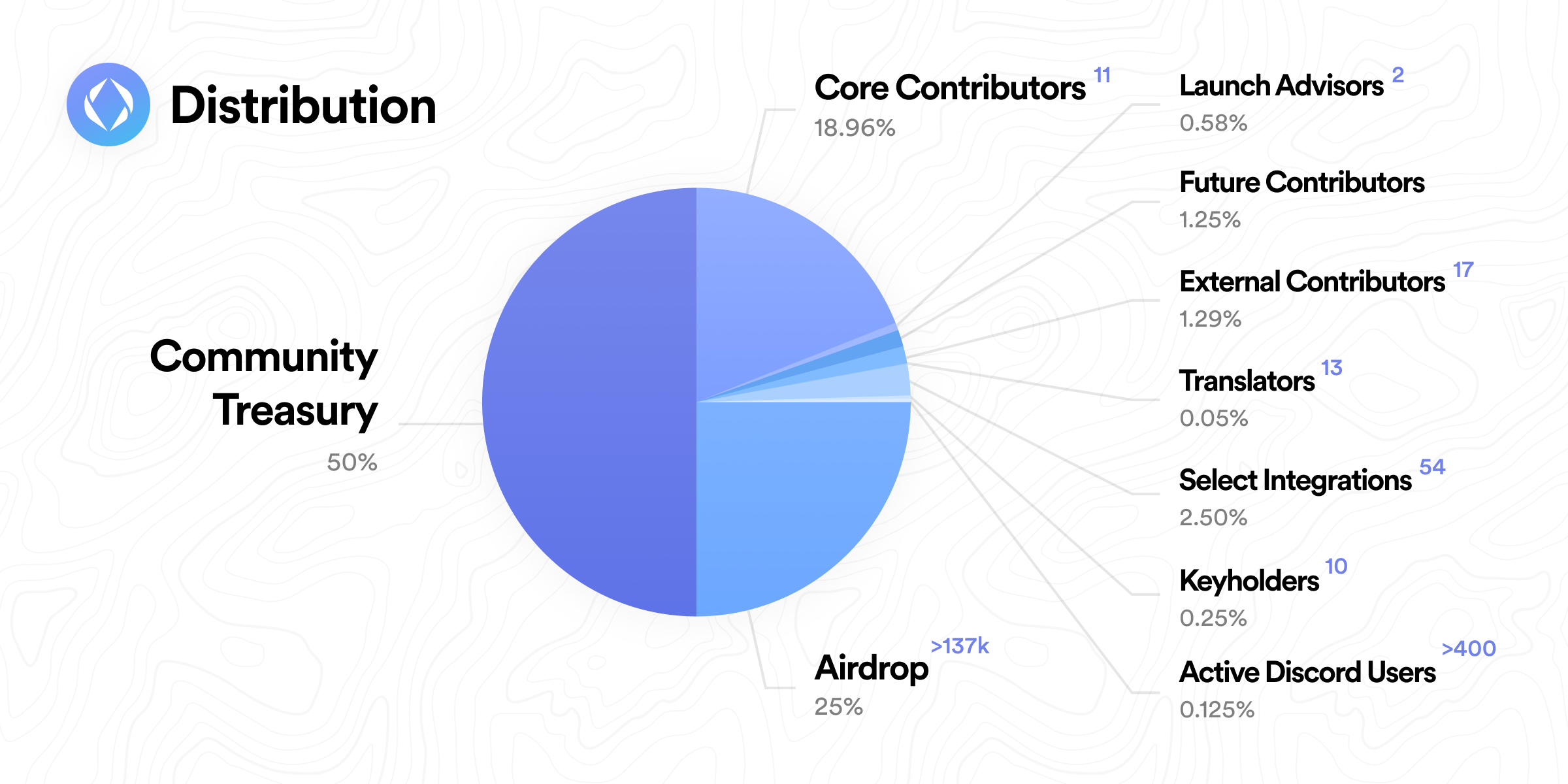

ENS is decentralized in the sense that multiple people - by all accounts, at least a few hundred - own it. This is a step up from seven keyholders! Congratulations!

ENS is not decentralized in the sense that there is binding, non-human, trustless enforcement of what you may consider to be desiderata, such as:

- not seizing people’s names

- not jacking up fees on the people’s names once they’ve invested into them (e.g. in terms of infrastructure)

- ensuring that insiders don’t get to register names for free (since the fees go back to them)

I can actually prove this. I took these examples directly from the “ENS DAO Constitution,” which is a “set of binding rules that determine what governance actions are legitimate for the DAO to take”.

Note here that, when they use words like “binding” and “legitimate,” they do not mean it in the technical sense. Nothing actually prevents a proposal from doing any of those things - that’s why they have their constitution. (If it weren’t technically possible to do something, why would they need to write a rule against it?) Indeed, as long as a proposal gains more than 50% of the votes with a 1% quorum, it can execute abitrary code on behalf of the DAO - even such code that will give anyone dictatorial control over it in perpetuity.

Is it censorship-resistant, then?

ENS is censorship-resistant in the sense that nobody can directly seize your domain.

ENS is not censorship-resistant in the sense that renewal costs are guaranteed to be stable or even consistent. If the people who own the DAO want to, they could crank up the fee for renewing only your name to $1,000,000,000, and then allocate it to whomever they please once it expires.

In other words, if your ownership of a name is prejudicial to the financial interests of the people who own the DAO, you might get a first-hand tour in what property rights actually mean. I’ll assume that they’d vote to clean out child porn4 - to do otherwise would surely result in disastrous headlines, and presumably cause for the token to drop in price. Likewise for “hate speech”. In the end, you’ll never know until you try it! Maybe it’s safe, maybe it isn’t! Hate to find out!

To put it even more bluntly: You “own” your domain, but you do not own your ownership of that domain. Your property rights exist only within the ENS system, and that system is in turn owned by what, in practice, forms a trusted third party. That system is the real owner of the domain; you merely lease it from them at a price that they are free to set.

It’s also worth noting that when I use the term “owners,” I’m being a bit loose. Actually, anyone (even you, dear reader!) can borrow some ENS and vote with it, for example using a flash loan contract or some more sophisticated system. This would probably allow you to obtain the votes you need for a quorum at little to no cost - if I understand correctly, you could borrow 0.4% of the outstanding supply right now off Uniswap for not more than the cost of the transaction. And if you have some more money, nothing prevents you from simply bribing people to vote for your proposal, except their own self-interest, which can be solved by yet more bribes.

It seems, then, that the strongest motivators any ENS holder would have to not expropriate your domain are:

- fear of real-world consequences (lawsuit, murder)

- concern that the price of the token will drop

- altruistic/ideological motivations (pride, honor)

It’s worth noting in this context that (2) is limited by two factors:

- You can always hedge the risk that your token will fall in price on DeFi markets. For example, if you have 100 ENS and want to vote “YES” on a disastrous proposal, you can always just sell 100 ENSUSD futures and be totally indifferent toward the price. Heck, you could sell 200 ENSUSD futures and have an incentive to cause the price to go down, while keeping your right to vote. (Modern joint-stock corporations have bylaws that prohibit you from voting on a company that you’re shorting. This is not possible in crypto, for obvious reasons.)

- If the bribe is big enough, the risk that the price will crash is not really important.

In other words, the ultimate guarantors of the supposedly “trustless” system are the real-world legal system, as well as people’s good faith, honesty, and reputation.

If you consider this to be censorship-resistant, then ENS is absolutely the token for you!

https://mailarchive.ietf.org/arch/msg/dnsop/-9zBqWpvNBlekGotR211s1mf6tM/↩︎

https://medium.com/the-ethereum-name-service/why-ens-doesnt-create-more-tlds-responsible-citizenship-in-the-global-namespace-7e66658fe2b1 - “Moving forward, we want to be as responsible as we can. This includes possibly seeking to register .ETH through the normal ICANN process” - note that the “normal ICANN process” for gTLD regitration requires compliance with trademark law.↩︎

I’m not saying they’d necessarily be morally in the wrong here. Child abuse is well into hostis humani generis territory, and I don’t think I’d act any different if I were given the choice. But that’s why I, unlike certain other people, am not in favour of giving to people this kind of power.↩︎